Sacred art supports truth, beauty of the liturgy

Yelling at the top of our lungs and jumping up and down may be acceptable at a sports venue, but in most other buildings we have a very different comportment, depending on the building. Our dress and our behavior are different whether we are in a doctor’s office, grocery store, mall, school, library or museum. We use our inside voices, dress and behave appropriately and practice self-control. Talking with a friend over a casual lunch is different from a job interview. In other words, we respond to the places and situations we find ourselves in.

Yelling at the top of our lungs and jumping up and down may be acceptable at a sports venue, but in most other buildings we have a very different comportment, depending on the building. Our dress and our behavior are different whether we are in a doctor’s office, grocery store, mall, school, library or museum. We use our inside voices, dress and behave appropriately and practice self-control. Talking with a friend over a casual lunch is different from a job interview. In other words, we respond to the places and situations we find ourselves in.

The placement of art and how we respond to it is no different. Religious art can have a subjective representation of a religion recognizable to some (such as home altars or T-shirts), but since sacred art is in our churches to support the liturgy, it must be a faithful representation of Catholic truths, recognizable to people of faith. The art must be based on sound theology; the truth is to be recognized as beauty. The Suida-Manning collection at the Blanton Museum in Austin has several masterpieces of sacred art and is well worth visiting, but the setting of a museum is different from when those pieces were in the churches they were painted for.

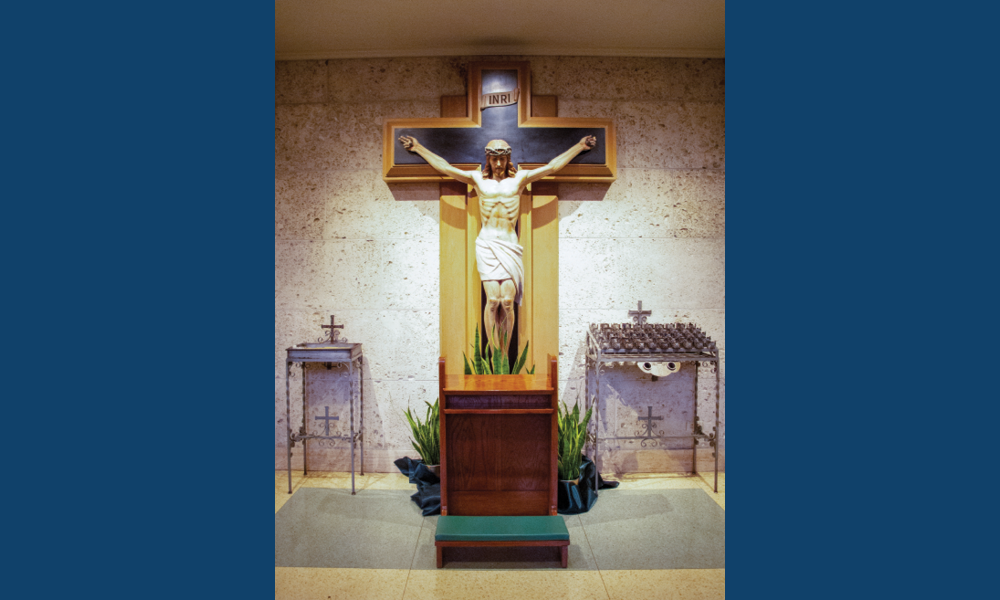

Imagine this image of a crucifix in a museum with a description of the artist's name, date when created, materials used, the name of the church where it originally hung and possibly the museum donor's name. As a monument to the past displayed in a museum, your response would probably be that of appreciation and recognition of the skillset of the artist. Now look at the image again and imagine kneeling in church and looking up to see Christ looking straight into your eyes. Viewing Christ’s face in that church setting, one’s immediate response would most likely be prayer. The church supports the truth and beauty of the art, just as sacred art supports the truth and beauty of the liturgy in the church.

As we look at art in our local parishes in this column, we must remember that we are participating in the universal communion of the faithful. In The Spirit of the Liturgy, the late Pope Benedict XVI stated, “God has acted in history, and entered into our sensible world, so that it may become transparent to him, images of beauty, in which the mystery of the invisible God becomes visible, are an essential part of Christian worship.”

What a beautiful expression: “the mystery of the invisible God becomes visible.” That is what sacred art does, but we need more than our eyes to see.

I invite readers to spend time with the art in their local parish. It is there for a reason.

Mark Landers is a parishioner of St. Austin Parish in Austin and a member of the Diocesan Fine Arts Council. He and his wife, Christina, own and operate Landers’ Studio, a woodworking shop and design studio. They design and construct custom furniture and high-quality architectural piecework.